Design Thinking Fellow

RBC•

Sept 2025 - Nov 2025

Context on the program

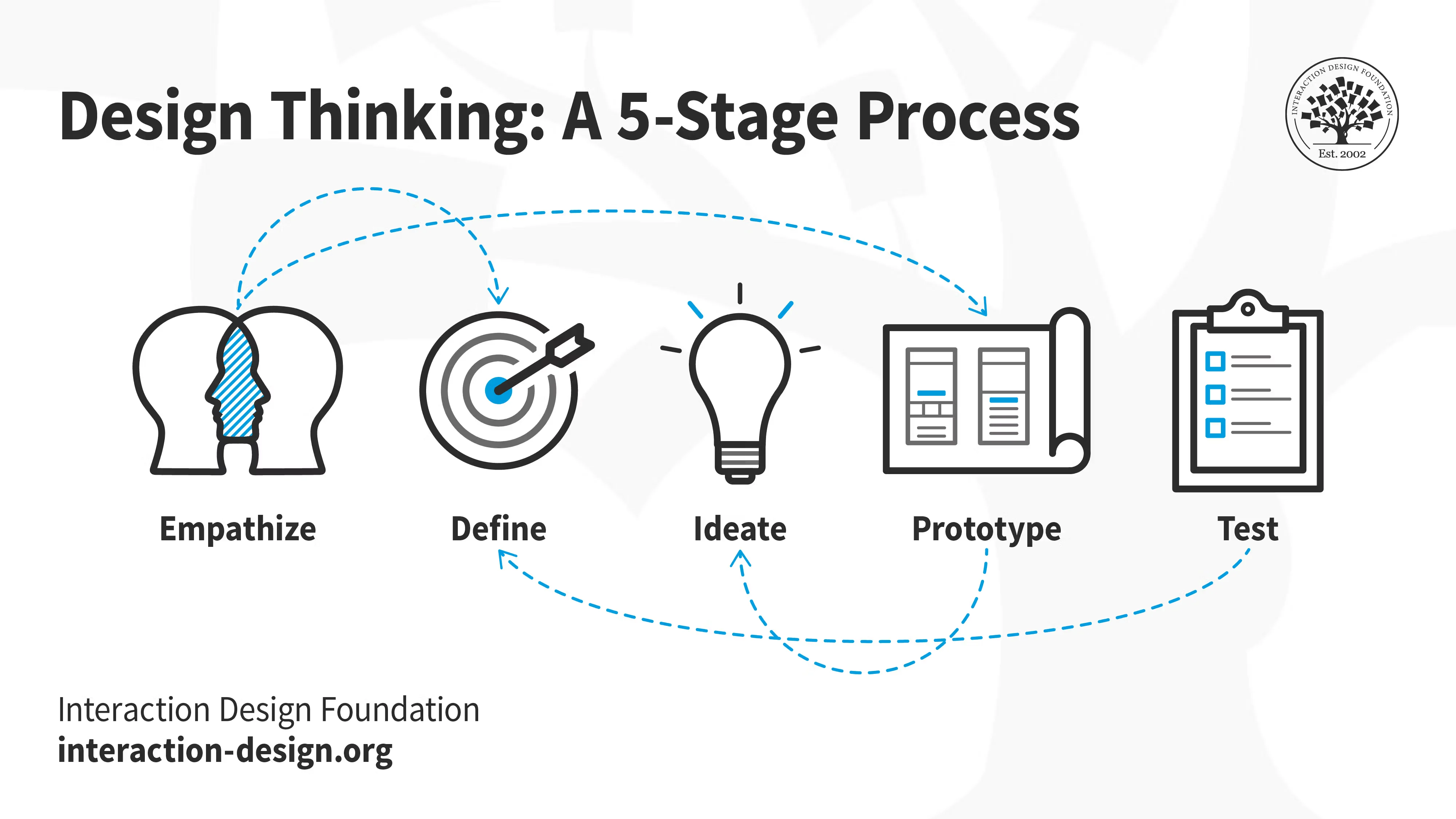

When beginning this deep dive, it is important to explain what the Design Thinking Program is. It is hard to summarize the program into one sentence, so the following is a brief summary:

The RBC Design Thinking Program is a fellowship that brings together 32 juniors to solve the central question: how can emerging technologies be integrated into non-technical sectors in order to drive Canadian prosperity? Over the course of the program, students are divided into teams of four, identify a concrete problem, develop a solution, and present their work to Western University leaders and RBC executives, all while being supported by feedback from RBC mentors.

Application Process

I had heard about the RBC design thinking program all the way back in my first year of university. Going into my third year, I knew that I wanted to get into the program, but I also knew how competitive the program was. Every year, the program gets more than 350+ applicants, and with only 32 spots, the acceptance rate is extremely low.

The application consisted of two rounds: an initial written application and a group interview. To my surprise, I managed to make it past the written application and onto the group interview. Determined to get in, I rigorously prepared for the group interview, brushing up on behavioural questions and reaching out to several seniors to gather intelligence. My work paid off, and I was thrilled to get into the fellowship.

Orientation

I still remember the first session of the program. It was on a Saturday from 10 to 4, a 6-hour orientation session. I remember going into the program I had felt nervous, but that nervousness quickly disappeared when I met the other people in the program. Everyone was super friendly, and I quickly felt at ease.

During the orientation, I met my three other group members with whom I would be closely working with for the next couple of months. What I liked about the program is how each person on the team had a unique skill and perspective. In Computer Science, I am always working with highly technical people, so working with different disciplines was like a breath of fresh air.

Identifying a problem

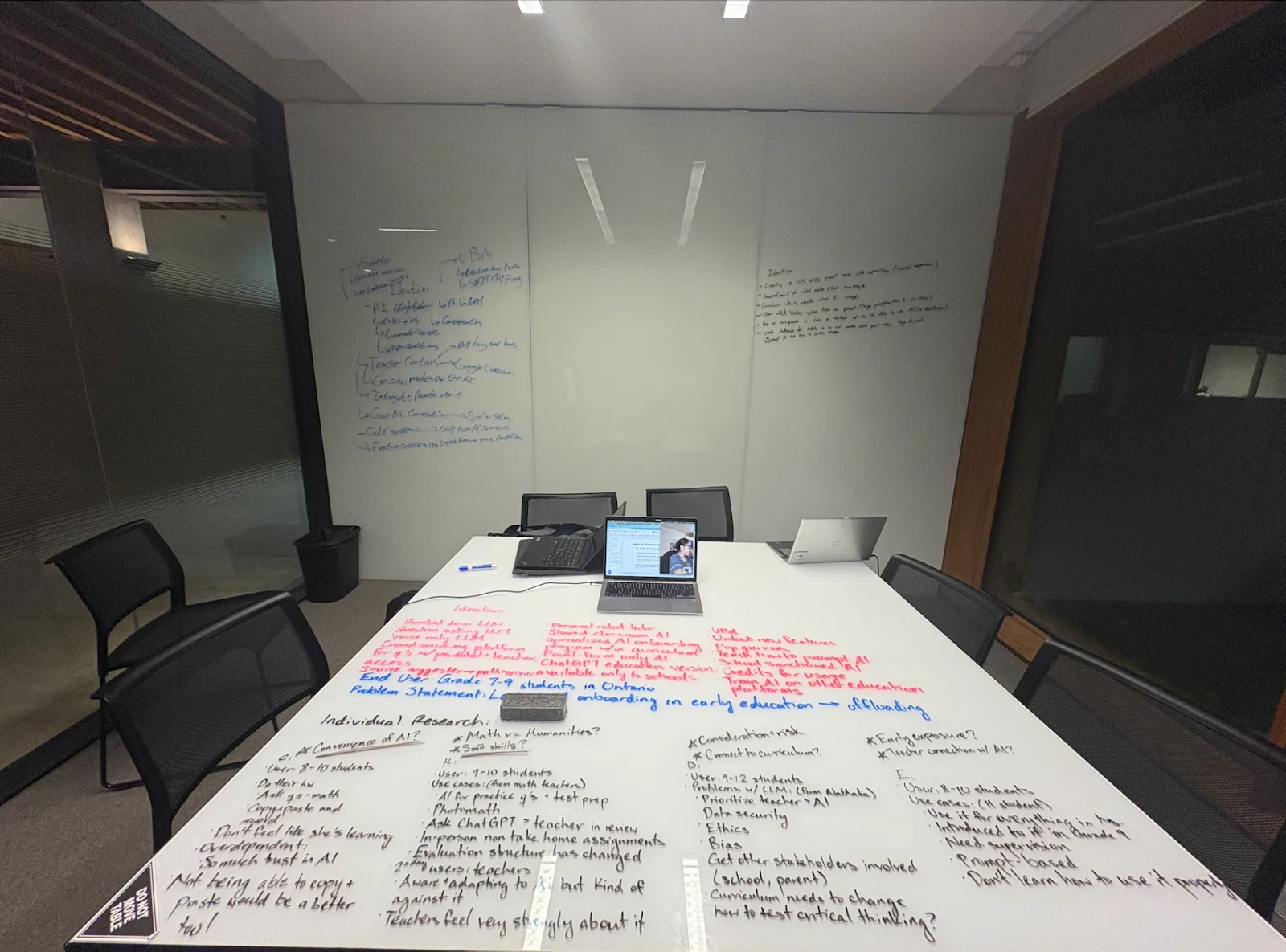

After some initial brainstorming, my team quickly settled on focusing on the topic of AI in Education. We found this topic attractive because, as students, we can easily relate to it, and we were curious about how AI was affecting younger students.

We spent the first couple of weeks brainstorming, and we quickly discovered the problem of cognitive offloading. Cognitive offloading is when a student offloads all critical thinking to an AI. For example, instead of writing an essay, a student would simply have an LLM do it for them, no critical thinking required. In the short term, students might feel as if they are getting ahead, but in reality, they are just stunting their ability to think critically. I find this to be a scary thought; if the next generation does not know how to think, how are they supposed to make Canada prosper?

To further understand the issue of AI in education, our group interviewed many students, teachers, school board trustees, curriculum experts and even Mark Daley, Western’s Chief Artificial Intelligence Officer. These user interviews were alarming to say the least.

From students, we learned that there was a competitive pressure to use AI. Students felt the need to use AI in order to help them get into university; if they did not use AI, they felt that they would get left behind.

From teachers, we learned of two pressing issues. First, students were becoming less socialized. One teacher told us about how he was hosting a work period and instead of asking him questions, students were opting to simply ask ChatGPT. Teachers further reported that the social skills of students had become significantly worse, with students often unable to respond, make eye contact and just kind of staring into the distance during conversations.

From school boards, we learned how much they were struggling with AI adoption. That the school boards were years behind and had just recently begun adoption. With no support, teachers were often relying on adhoc methods to ensure learning in their classroom, such as making all essays hand-written in class.

From Mark Daley, we learned that the AI problem was a values problem. Halting AI use is an impossible task; instead, we should focus on instilling values in students that make them want to learn.

The user interviews painted a grim picture. Every level was struggling with AI adoption, and this revelation led us to our problem statement: The lack of AI onboarding in early education has led to students mindlessly offloading critical thinking tasks and social engagement.

Ideating our Solution

With the problem in hand, we began thinking of potential solutions. We knew that AI could provide immense value to education; every kid now had a personalized tutor. Banning AI would not be a tenable solution.

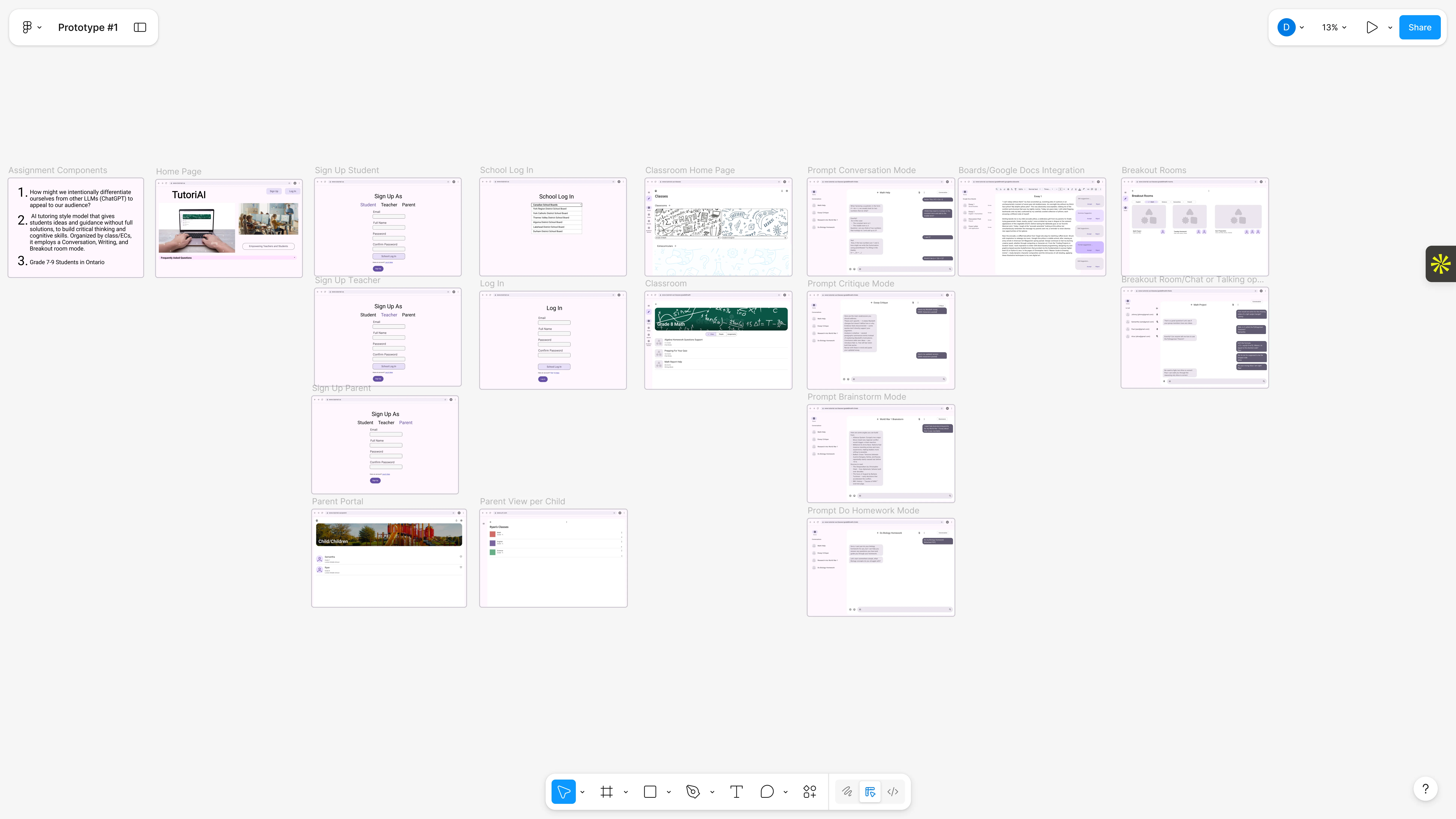

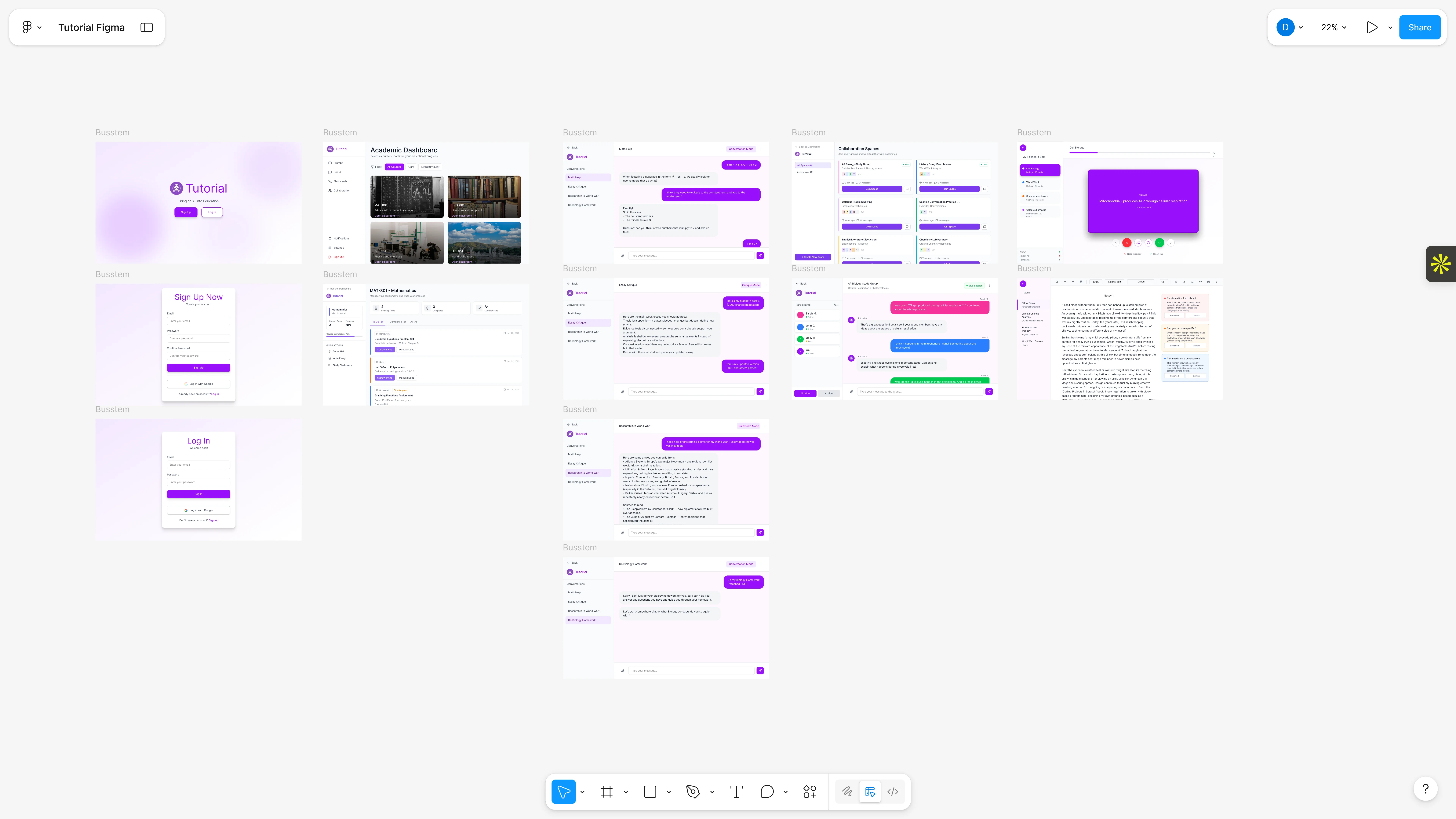

With this lens in mind, we locked ourselves in a study room and wrote down as many ideas as we could think of. In the end, we came up with 17 unique ideas, which we combined to create Tutorial. We envisioned Tutorial as a Google Classroom + AI chat designed to empower students, teachers and parents. Tutorial tackled cognitive offloading by restricting AI to certain conversation archetypes that promote critical thinking. Instead of giving the answer, Tutorial would slowly guide students to the solution by asking them thought-provoking questions. Our app would act like a tutor, and being a tutor does not mean writing an entire essay for a student.

Tutorial further included an in-built classroom where teachers can monitor students, assign homework and post lessons. Having the classroom directly on Tutorial was powerful; it enabled us to feed lessons as context, increasing personalization, but also allowed the school to monitor and incentivize the use of our app. Having a solution in mind, we set out on prototyping and receiving feedback.

Prototyping and Feedback

The next step of the design thinking program is prototyping, and over the fall reading week, we began creating our prototype on Figma. The first prototype was essentially a wireframe that mapped out our core features and the interactions between different pages of our application. It was created to be a punching bag for feedback. We wanted people not to be lost in the visuals, but instead focus on the idea behind the prototype.

The feedback we received was very positive; people thought that our product was great. One point of constructive criticism, however, was that our product was focused on too many groups. We were targeting students, parents, teachers and schoolboards causing to us not having a coherent target audience. The criticism was valid; our group was having an identity crisis; we were split on whether to target students or school boards. Figuring out who to focus on was not an easy decision; it was a question of either a top-down or a bottom-up approach to the education system. I was firmly in the top-down camp; I believed that the only way to get real users was to get the school boards on board. Half of the group was on the bottom-up approach; they believed that making the product great for students was the correct approach. The group was in a deadlock.

Our initial approach to the deadlock was to ignore it, and we continued refining our product. Sweeping the problem under the rug was not a good solution, and as the final demo day kept getting closer, I decided to find a compromise. After a lengthy discussion, we decided to do the bottom-up approach, but as a middle ground, we would repurpose many of the top-down features to be great for students. The compromise worked; our group was in a great position heading into the final 2 weeks of the program.

That confidence was shattered one week before the end of the program during our practice pitch. One of my teammates was unable to attend, and I had to step in and deliver his portion of the presentation. The feedback we received was direct: our slide deck was visually distracting, the demo video moved too quickly, and our presentation lacked coordination as a team.

I pushed our team to take this feedback seriously. We redesigned the deck to be more minimalist and focused, replaced the demo video with static images to allow for greater flexibility during the presentation, and scheduled additional rehearsals to improve timing and cohesion. These changes allowed us to present more clearly and confidently as a team.

Our efforts paid off.

Final Pitch

On the final day of the fellowship, we presented our prototype to a room of Western and RBC leaders. The audience responded positively, praising the clarity of our problem framing, the focus of our prototype, and the professionalism of our delivery. I felt extremely proud in what my team and I were able to accomplish.

Reflection

Reflecting on the Design Thinking Program, I am deeply grateful for the opportunity to have participated. The experience fundamentally changed how I approach problem-solving. Previously, I often believed I understood the full picture and rushed toward solutions. The program taught me the importance of first developing a deep understanding of the problem itself. By learning to prioritize user understanding and thoughtful problem definition, I developed skills in design thinking and product management that will continue to shape my future endeavors.